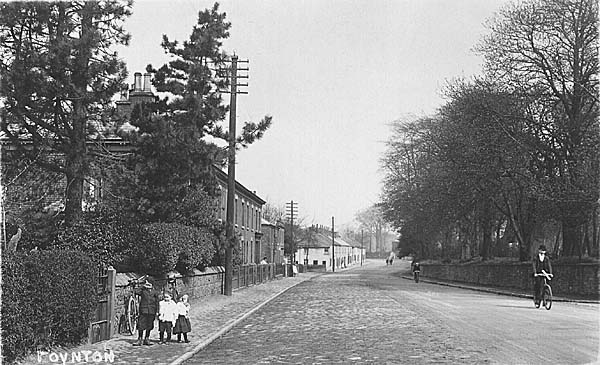

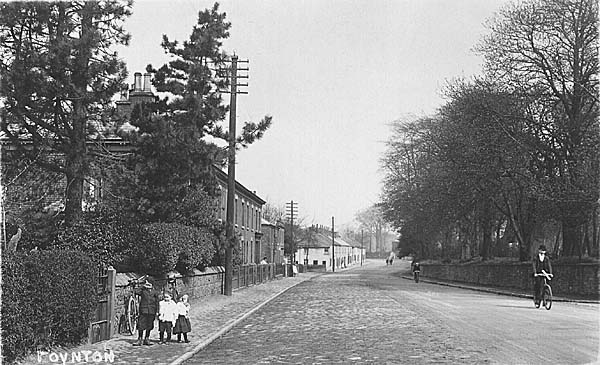

London Road North, 1906. White cottages, now demolished,

were part of the old "Village".

Photo © John Ryan collection

This chapter is divided into three parts, namely accounts condensed from the longer reports on; first the physical development of roads, in the district; secondly the early attempts to bring canal transport to the service of the coal and other trades; and thirdly the nature of the goods, mail, passengers and operators of road and water transport. This includes especially the development of the world famous firm of Pickfords, which started in Poynton, until the 1840s, when the last Pickford connection ended.

Roads

If we look therefore at road transport first in the early eighteenth century, in this area there were no well maintained through roads, but rather winding country roads and cart tracks which went from one village or hamlet to the next. The system of road maintenance established in Elizabethan times required voluntary parish or township surveyors of the highways or waywardens to maintain their local roads with the aid of a small highway rate and a system of statutory labour i.e. vehicles, men and materials, provided by the richer folk who were liable to pay rates. The work was supervised by local churchwardens and JPs and enforced in Quarter Sessions meeting at Knutsford. For example in 1722 a local J.P. J. Davenport when unable to attend through gout reported to the Sessions.1

"I have viewed the Roads lying within the several Townships of Dean Row, Woodford, Poynton and Worth and find that the inhabitants have been very industrious and have prepared materials for repairing the same, but the season having been wett have not had time to perfect them so well to be certified".

He pleads for more time. Also in 1741 Edward Wood of Worth was presented for not repairing Hepley Lane (his tenure made this his responsibility) containing 250 yards in length and eight yards in breadth.

At this time there was already an increasing amount of traffic and an extensive land carrying system had been built up throughout the country - especially needed to transport the finished products of the textile and other trades in the Manchester area to the Midlands and London and bring in raw materials. There was also a considerable traffic of stone and timber from east to west through Cheshire with backloads of salt - partly using the old Roman road (still called the Street) through Adlington and leaving names such as Saltersford to mark its course - see Dodd's interesting book.2 The effect of this traffic especially north to south on the inadequate roads was to wear them out more rapidly. Thus one traveller, Arthur Young, described the roads on the Cheshire plain in 1771 as "cut into perpetual holes, some two feet deep, and the rutts and holes most execrable".3 The nature of these roads may be glimpsed in the medieval side roads which still survive between ancient hedges which can be dated, e.g. Wych Lane and Hope Lane, of the 13th and 14th centuries, shown on a map produced by the Adlington Womens Institute.4 Because of mud and ruts in the summer and snow and ice in the winter on lower routes across the Cheshire plain the most important route to the south was that through Bullock Smithy (Hazel Grove), Buxton and Derby (present A6). John Ogilby in his famous road atlas shows this in 1675. This was one of the earliest roads to be improved by the formation of a turnpike trust in 1724 which charged tolls to pay for widening, straightening and improving the surface. Being on hillier ground it was better drained. At this time there was no direct route through Poynton between Stockport and Macclesfield - a road, the present Chester Road, turned off the A6 in Hazel Grove and wandered via Dog Hill Green, Woodford and Adlington Hall to Macclesfield. Before the new turnpike road was made in 1762 a branch off Chester Road from Hazel Grove went to Poynton Lane Ends (or "the Village"). From there also was the main entrance to Poynton Park. The road continued to Poynton Green, whence one road went east to Lyme Hall and Disley while another (now Clumber Road) continued to join Dickens Lane and then turned via Birches Farm to Adlington, joining the other road at the ancient Hollingsworth Smithy. Another branch from Woodford went westwards to Dean Row and Wilmslow. We know that the Domes and Warren families sent out coal this way and petitioned Quarter Sessions in 1611 to have it properly opened "as those that travel that way and the transport of coles is suffering".

In the 1760s three forces came together to produce a permanent improvement. Sir George Warren decided to beautify and improve his Poynton estate by building a new hall, getting John Metcalf, the famous blind road builder, to lay out new roads, for which he paid him£1000, and create an ornamental pool with landscaping. At the same time many business interests in Leek and Macclesfield were anxious to improve communication for their manufactures using a lower route which would be more free from snow and ice in the winter and would skirt the edge of the Cheshire plain. In 1762 they surveyed a route from Bullock Smithy on the existing turnpike to Sandon in Staffordshire which lay on another main route south of Newcastle on the present A34, and put forward a bill which Parliament enacted. They described the existing route as "deep and ruinous ..... narrow, and cannot be sufficiently widened, altered and repaired by the ordinary course of events".5 A large number of trustees were formed to manage the road including the Leghs of Adlington and Sir George Warren. Thirdly, as will be described, a new road carrying business based in Poynton was being built up by James Pickford between Manchester, the Midlands and London; he obviously was a strong supporter of any improvement on the main road through Poynton.

The road was completed in the early 1760s and in our area included for the first time an improved route direct from the Rising Sun in Hazel Grove to Poynton Lane Ends with an improved bridge over Norbury Brook near which the most northerly toll bar was set up to catch traffic on the road. It used the new embankment which ran in a straight line north to south and formed the western bank of the new Poynton Pool, a section called the Crescent being cut out to provide a new coal yard for Sir George's coal business, (see Chapter 10). It then continued direct to Birches Farm to join the older route via Poynton Green and Dickens Lane and crossed Poynton Brook. At this time there was no Park Lane or Chester Road, but a new chapel was built in 1789 at what came later to be Fountain Place.

The original tolls on the road taken from the Act were as follows:

"For every Horse, Mare, Gelding, Mule or other Beast laden or unladen and not drawing, the Sum of One Penny. For every Drove of Oxen, Cows or Neat Cattle, the Sum of Ten Pence per Score, and so in proportion for any greater or lesser number. And for every Drove of Calves, Hogs, Sheep or Lambs, the Sum of Five Pence per score and so in proportion for any greater or lesser number."

This shows traffic consisted of carts of various kinds, passengers on horse back, packhorses and droves of animals. There was a further toll bar at Tytherington to catch traffic to and from Macclesfield and side bars at Poynton Lane Ends to catch Wilmslow bound traffic from Poynton and at Butley. Sir George Warren secured a half price rate for his coal at these local bars. The old statute labour system of maintenance continued at first but gradually the townships agreed to pay a financial contribution in lieu for upkeep of the road, (£4 19s 6d paid by Poynton and Worth in 1822), until statute labour was abolished in 1835. The only surviving toll house is at the end of Robin Lane, Macclesfield on the side road to Sutton.

Milestones were set up, originally made of rough stone, but between Macclesfield and Stockport about 1824, when this section of the road came to be administered separately, cast iron metal plates were set up giving the distance to London (which the trustees were anxious to advertise) as well as to Stockport and Macclesfield. Five out of the original eight are preserved, one near Anglesea Drive, one near Brookfield Motors, the best preserved at Hope Green, here illustrated, one at Millhouse by the railway bridge, recently repaired by Cheshire County Council, and one where the Prestbury road turns off.

As the minutes of the Trust show, in 1767 a glowing advertisement was inserted in the Birmingham and Manchester newspapers as illustrated. 6

Tolls were changed in later Acts, e.g. in 1803 and 1824, as experience showed the need to favour broad wheeled wagons which did less damage and take account of the stage coach and light flyvan traffic. Norbury remained one of the busiest bars; in 1802 for instance 20% of the whole takings occurred there. The right to take tolls was let each year for an agreed sum (which increased at Norbury from£350 in 1803 to£2060 in 1836, just after the heyday of the trust before the railways came). There was very much coal traffic to Stockport, Macclesfield (before the canal came in 1831) and mid-Cheshire, but some coal also went out via Middlewood to the Buxton road, though this was restricted by the Leghs of Lyme so as to favour their own Norbury Colliery coal. In 1810 there were considerable improvements which straightened the section from Hollingsworth Smithy, which had to be moved, to the bridge over the River Dean - now a pleasant tree-lined avenue - instead of the winding route via Adlington Hall. Relics of the old route may still be traced on the Adlington map. The coming of the Stockport-Macclesfield railway caused new sections of road to be built at Hope Green and near Millhouse Farm, also straighter. This left at Hope Green a small portion of the road fossilised as it was in 1845 which gives some idea of its width and character.

The bridges at Millhouse and Norbury had to be kept in repair, by the county authorities according to ancient custom, being subject to damage from floods as well as heavier traffic. For example there are records of extensive repairs to Norbury Bridge involving the creation of a new weir and stone foundations in 1824 and a new arch in 1828 built by Peter Worsley of Heaton Norris, wheelwright and timber dealer,7 with substantial covering to support heavy loads, total cost with other repairs £175 - the two arches can still be seen under the bridge.

The peak year for income from the Macclesfield section was 1826-7 when£9547 was received but then as the first railways came connecting the north with the Midlands and London, the Macclesfield canal opened in 1831, and other rival trusts such as the Manchester-Wilmslow-Congleton took more of the traffic (founded in 1791), our local trust began to decline, though coal traffic was substantial until the Macclesfield-Stockport railway opened in 1845. By 1846 income had fallen to£1449 and fell below£1000 by 1862. Railways were so much speedier and cheaper both for passengers and goods, stage coach services had ceased and road carrying was mostly local to serve the railways, or canal. In 1878 the trust closed, the toll bars were sold and the local Highway Board at Prestbury took on responsibility for the road.

The Cheshire map of Burdett, 1777, Poynton portion, here shown with the toll bars added, and the larger scale 1770 estate map of Poynton by Tunnicliff show the turnpike road and its feeding side roads before the 1810 and later improvements. Park Lane by 1777 had reached the main road at the chapel from Poynton Green, but the main route to the west from Poynton still lay via Lower Park Road from Poynton village. By 1819 Greenwood's map of Cheshire shows a new road then called Chapel Lane (now Chester Road) had been created, making the crossroads at Poynton Place for the first time the main intersection. The Park had been extended right to Park Lane and westerly across London Road, so that Lower Park Road became merely an estate road, its end secured by the Lodge still to be seen near the Woodford Road. In the 1840s when the trusts were in financial difficulties and road operators were protesting at delays and the payment of tolls Parliamentary Commissioners investigated the state of the trusts. In 1840 our turnpike was found to be "very good, no part under or liable to indictment for want of repair". After 1835 when statute labour was abolished, salaried surveyors were appointed and money payments in rates were exacted from the various townships - Poynton contributing£37 a year and Worth£10. The confusing story of the development of road administration down to the modern situation with the Ministry of Transport responsible for trunk roads and the counties for the others is told in Bird's book.8

There have survived among the parochial records of Poynton at Chester9 a highway ratebook for Worth from 1841-62. This lists the chief occupiers of property, its annual value, and their assessment for highway rate, mostly at 3d in the£, from£40-56 being raised annually. In 1846 the following interesting list of roads in Worth is included.

| Name | Paved Yards | Brokenstone yards | |

| From Worth Machine to Dalehousefold | 220 | ||

| From Worth Machine to Poynton Green | 766 | ||

| From Worth Office to Boundary below Smithfield Pit | 1170 | ||

| Part of Waterloo Road | 600 | ||

| From Worth Clough to boundary near Lower Anson Pit | 715 | ||

| From Worth Clough to boundary near Horse Pasture | 1267 | ||

| Total length paved road | 4798 | ||

| Total length broken stone | 220 | ||

| Total length of bye roads on Worth 2 miles 1498 yards |

The Worth machine referred to was for weighing coal. An example of one of

the roads paved with local stone is still preserved in Wards End.

|

|

|

London Road North, 1906. White cottages, now demolished,

were part of the old "Village". |

|

|

|

|

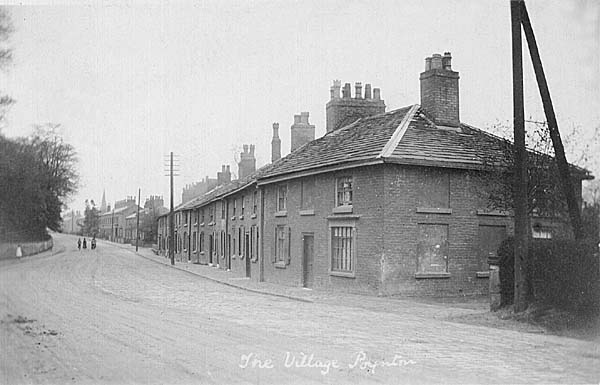

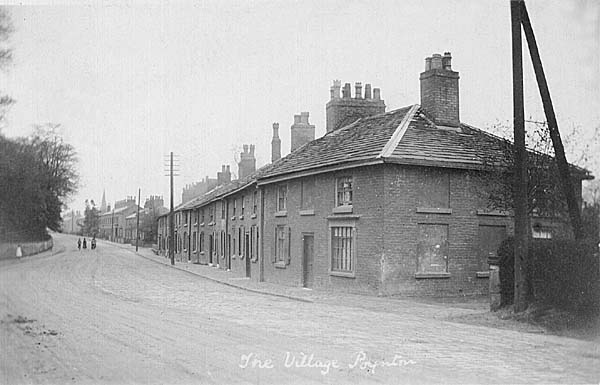

Poynton Village c1905. Photo

© John Ryan collection

|

From 1867 following a major Highways Act our local roads became the responsibility of one of the new larger highway districts, the Prestbury Highways Board which existed till 1894 when the new County, Urban and Rural District Councils took over in a reformed system of local government. Its records from 1879 are preserved at Chester along with the subsequent local administration of Macclesfield Rural District Council,10 responsible for all but county roads till 1974. The accounts show receipts from the districts, expenditure on salaries, wages, tradesmen's bills, materials such as stone, slag, sand, limestone, pipes, posts, piles and rails and the payment of manual labour. A map by Firth and Mitchell, surveyors, dated 1865 shows the Board responsible for all the roads already mentioned together with Coppice Road, Anson Road, Middlewood Road, Green Lane, Prince Road, Carlton Road, the road to the Vernon wharf on the canal and Shrigley Road to Needy Gate and the canal. Lower Park Road, Hig Lane and Elmbeds Road and Towers Road were not maintained. The first two gradually fell into disuse. The first Ordnance Survey Map on the large scale of 1: 10560 shows all these roads as they were in 1881. The local townships Poynton and Worth, combined in 1881, often complained about the state of their roads to the Board, e.g. Anson Road in 1881 and the need for a wider road and better footpath to the Poynton station which was moved from Midway to its present site in 1887. After 1894 the County took over responsibility for the former turnpike from the Highways Board and has gradually made considerable improvements; for instance its authority was stamped on the road by the new type of county milestones.

New problems were brought to the roads following the quieter period in mid century after the railways came. First were the heavy steam vehicles needing restrictive legislation on speeds and a red flag man in front, then bicycles needing lights and audible warnings, and finally most revolutionary of all, motor transport. This because of its greater speed and loads reduced the road surfaces to potholes, ruts and clouds of dust. Chesterman's book11 tells the story in Cheshire of the legislation on licensing and regulations concerning speed limits, and safety with the aid of excellent pictures of early vehicles, used by their Cheshire owners. In the twentieth century increased traffic gradually forced the metalling of roads with the aid of much more money raised from licenses and duties on petrol (from 1909). Road accidents became a serious problem by the 1930s leading to the 30 m.p.h. speed limit in 1934 in built up areas. The young Lord Vernon in the 1910s was several times involved in accidents in the early days of motoring - no doubt treating his car as a spirited steed. Road lighting also became more important. The Jubilee Fountain and Lamp Standard erected to celebrate Queen Victoria's Jubilee in 1897 both refreshed horses, other animals and people with water and provided gaslight at a very busy junction. The Parish Council acted as a ginger group to suggest road and pavement improvements, to the R.D.C. There was little major road improvement or the building of new roads in our area before the second World War except for Clifford Road. Most new building was on existing roads, though the first council houses built on either side of Dickens Lane in the 1920s required new roads on the "Dickens" estate, and minor roads such as Hilton Drive, Oak Grove, Park Avenue, Anglesea Drive, Bulkeley Road, Brookside Avenue, George's Road, Lostock Hall Road, Highfield Road and Lower Park Crescent appear on the 1935 edition of the 1:10560 map. Still in 1906 half of the main London Road was paved as the picture shows, and the pavement was also cobbled. The white cottages at "the Village" were later knocked down, but the cottages on nearside left and the Bull's Head are still there.

Canals

In the late eighteenth century after the success of the Bridgewater Canal, originally built to help transport the Duke's coal from Manchester to Worsley, many other industrialists and leading merchants were interested in building similar canals to transport heavy materials like coal and make them cheaper. Charles Roe, a silk manufacturer in Macclesfield, later a copper smelter, combined forces with Sir George Warren who was anxious to transport his coal more cheaply. Along with others they proposed in 1765 a canal joining Stockport via Poynton, Macclesfield and Knutsford to the Weaver at the point where it was navigable from the Mersey Estuary. It was estimated that the cost of coal transport to Macclesfield from Norbury and Poynton could be reduced from 7d per cwt to 4d. This proposal was defeated by a rival scheme and opposition in the House of Lords by the Duke. In the 1790s after Sir George had acquired the Worth Estate including its coal, several other canal schemes were put forward. Some offered links to the main market in Stockport e.g. a scheme involving two canals at different levels joined by an inclined plane near Norbury Mill in 1795, as described in Chapter 4. Further schemes included Macclesfield as well as Stockport in their routes and possible links with the Peak Forest Canal, which opened in 1800, in the north and the Midland canals in the south e.g. in 1811. These were defeated by lack of capital and the opposition of the Trent and Mersey canal to any plan which shortened the route to the south from the Manchester area and missed out some of their canal from Preston Brook.

One of the engineering difficulties of the situation was that in the 1800-1830 period the pits were relatively high compared with Stockport and it was easier to link them via a canal at the high contour at 518 feet with the existing Peak Forest and Ashton Canal system in the north, thus giving access to Manchester but only a roundabout route to Stockport. Macclesfield is also high at the Buxton Road side so could be reached by a canal on the same contour. Eventually in 1826 and almost too late, for the railway era was very close, a successful scheme was promoted and a canal opened in 1831, chiefly designed to put the growing industry and population of Macclesfield and Congleton on the map. Lady Bulkeley offered necessary land at the time of the Bill, and Thomas Telford late in his career was the architect. The links with the Peak Forest Canal in the north and the Trent and Mersey canal at Hall Green were constructed so that neither existing canal lost water. The bridges, aqueducts, wharves, pounds and weirs were beautifully constructed in local stone.

Telford believed in long level stretches with a concentration of 12 locks at Bosley to bring the canal down and across the Dane Valley. The canal was built to take narrow boats seven feet wide and was 16 feet wide at the bottom and 5 feet 3 inches deep. Elegant turnover bridges allowed horses towing to change sides and the stones in the skewed bridges had each to be specifically designed to fit the plan. Milestones at the mile, half and quarter were erected; some have survived though the distances to Hall Green and Marple have been obliterated for reasons of wartime security. The cost was£320,000. Full details of the bridges, water supplies from Sutton and Bosley Reservoirs, with a feeder stream also from Poynton Brook, near Mitchell Fold, locks and towpaths are given in the British Waterways Board's Cruising Bulletin No.11 12 and Nicholson's Guide to the Waterways No.3, North West.13 Main repair shops and yards with a side channel entering a warehouse were established at the Marple end of the canal where also Jink's boatyard on the Peak Forest Canal could be used for repairs. The original tolls were fixed as follows in the Act.14

"For every Ton of Sand, Gravel, Paving Stones, Bricks, Clay, Coal for

burning lime, limestone, and Rubble stone for Roads, the sum of One Penny

per Mile: For my Ton of Ashes, Stone, Slate, Flags, Spar, Coal (except for

burning Lime) and other Minerals, the Sum of Three Halfpence per Mile:

For every Ton of Timber, Lime, Goods, Wares and all other Merchandise,

Articles, Matters and Things not mentioned above, the Sum of Two pence per

Mile." There was provision for the licensing and registration of boats

to carry passengers.

The canal was opened 18 November 1831 ominously only months after the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. The Stockport Advertiser thus describes the event:

"There were two processions of boats, one from the north end (25 boats), one from the south (52). The leading boat of each division was occupied by part of the Canal Committee, the Proprietors and their friends,- immediately after followed a band of music, then the boats of the Committees of other canals; then came the pleasure boats of such gentlemen as joined in the procession and lastly the trade boats in order of their arrival, fifty of them containing 1000 tons of coal and the remainder carrying grain, salt, iron, timber, lime, coke, bales of cotton, groceries and other merchandise."

Banners flew from boats and buildings, artillery sounded and finally about 200 walked in procession to the new Town Hall at Macclesfield.

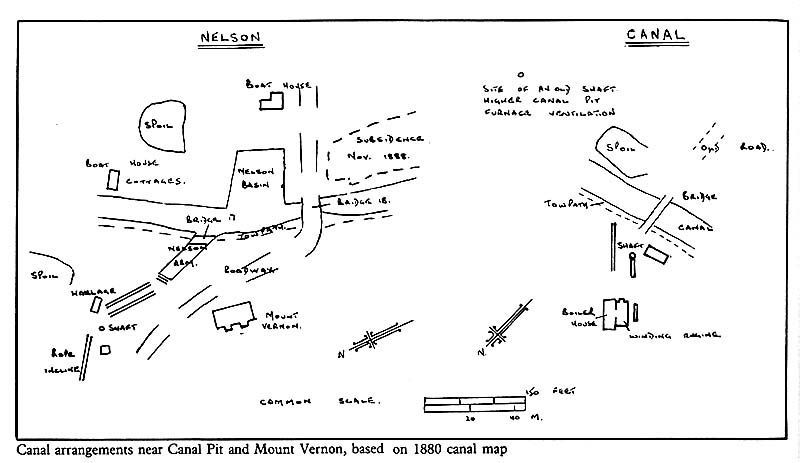

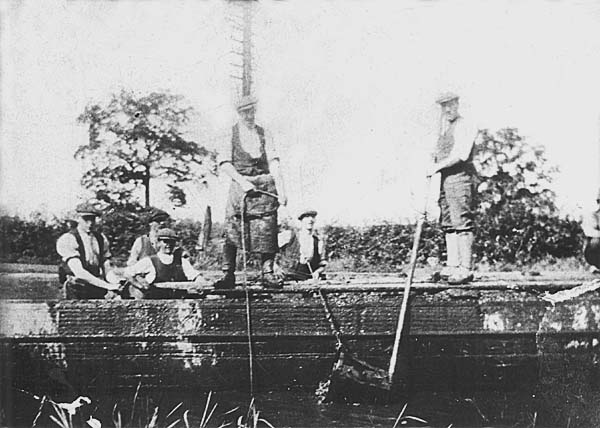

Special physical and commercial arrangements were made to suit colliery owners near the canal and throughout its life coal was the principal single item carried. Arrangements were made to allow mineowners to continue their underground mining subject to adequate supervision by canal engineers and compensation where coal or other minerals had to be left in situ so as not to endanger the canal. There were still subsidences especially in the vicinity of Nelson Pit where the wide lake known locally as the Wide Hole adjoining the canal near the present marina at Mount Vernon was formed before 1871, and subsequently enlarged by further subsidence. It was a continual job for a team of workmen to stop leaks, repair banks and bottom. As the map shows a wharf was built at Mount Vernon with a branch canal leading to it under a towpath bridge. The same stone and building style was used; connections were made with nearby Nelson Pit and via a rope hauled tramway with Anson Pit alongside Anson Road. Here coal was loaded in to narrow boats which could be assembled in a pool on the opposite side near which were a boatbuilder's shop and repair facilities, boathouse and stables. These are clearly shown on the 1849 Estate Map. There was also a lime kiln fed by lime brought via the Peak Forest and Macclesfield Canals for agricultural and building use. The picture by R. Walton shows coal from the Lawrance Pit being unloaded from tubs by means of a tippler into boats in the 1930s at the Vernon Wharf. The boat shown belonged to the collieries and was known as a day boat since no one lived on it at night, being still horse drawn - the chimney was for the cabin stove to keep boatmen warm in cold weather. Coal for loading came from Nelson Pit 1860-80 from Anson Pit till it closed in 1926 and thereafter from Lawrance Pit via Anson Pit railway sidings.

|

The colliery itself owned 20 boats carrying 20-30 tons each on the canal in

1847 with 14 boat horses and a staff of two boat builders, five boat loaders

and 28 boatmen. Many of the men lived in the Mount Vernon area. This was the

peak number - traffic declined later as rail connections were improved, but

up to the 1870s Mount Vernon must have been a very busy wharf as no doubt some

of the canal company's own boats called there and other companies used their

own boats to collect coal. During the 1926 strike miners used colliery boats

to comb the bottom of the canal with rakes and wire draglines to recover coal

which had fallen in over the years. The photograph of this is the only known

surviving picture of a colliery coal boat.

|

|

| Miners combing the canal for coal during the 1926 strike. |

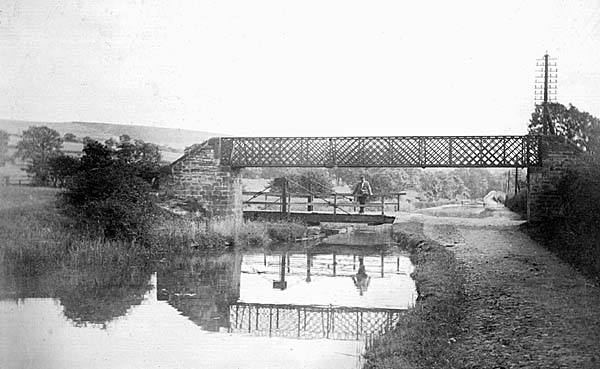

The Canal Pits, Higher and Lower, were on either side of the canal. Coal was brought from Dingle Pit and Higher Canal Pit on the east side by tramway to the canal and a basin is shown on the 1871 1:2500 O.8. map here. These pits operated from 1820s - 50s. On the west side Lower Canal Pit may have sent out some coal by the railway connecting with Prince's incline after it was opened but the canal became the main route during the period 1840-90 after which the shaft was retained for water pumping purposes. There were two boatloaders employed there in 1881. Various bridges over the canal are shown on the maps at this point. There were lattice girder foot bridges in the local area associated with swing bridges for cattle and vehicles to cross. Many are now abandoned but a lattice bridge and traces of swing bridge survive north of Mitchell Fold.

There were many other wharves to serve collieries and quarries, eg at Middlecale, at High Lane (for Norbury coal), at Adlington and opposite the Adelphi Mill in Bollington for Kerridge stone: at High Lane a large L-shaped branch was built by the company with a warehouse, crane and a variety of berths - now used as the Headquarters of the North Cheshire Cruising Club, one of the early pleasure cruising clubs established in 1943. This was used by road carriers such as Pickfords who at their peak owned 398 boats on the canals - for example hats in barrels were brought by them from Christy's works in Stockport by road to be put on boats there for transport to London. In the 1840s also many other companies operated public carrying facilities on this canal e.g. Kenworthy and Go. and J.P. Swanwick and Co., who brought miscellaneous goods including raw silk to Bullock's mill in Macclesfield.

There was a small amount of passenger traffic - for example in 1842-6 one

boat ran each way weekdays (three on Sundays) Macclesfield to Ashton in the

morning and evening. A poster shows how both commercial and leisure traffic

was hoped for, linking with the train services from Dukinfield to Manchester.

But the opening of the railway to Macclesfield in 1845 and the sale of the Canal

Company to the Sheffield, Ashton and Manchester Railway Co. along with the Peak

Forest and Ashton Canals led to a decline in passengers, despite some attempts

by the new owners to foster it. Pickfords entirely withdrew from the canals

in the 1840s. Some girls travelled to work in mills in Marple and Bollington

from Poynton but the opening of the Macclesfield, Bollington and Marple Railway

in 1869 with its stations at Higher Poynton and Bollington brought this to an

end.

|

|

| Hagg Bank lattice girder bridge, swing bridge and bridge over side arm towards Redacre. c1900 |

The commercial importance of the canal in general arose in its early days from the fact that it offered a new route from the Manchester area to the Potteries and further south which was ten miles shorter than that via Preston Brook and the Trent and Mersey Canal, but with 20 more locks. There was fierce rivalry and price cutting between the alternative routes in the 1830s and the price of transporting coal came down to 0.75d per ton per mile. At this time the canal made a very significant contribution to coal sales from Poynton. 73,215 tons were sold in 1830 and this jumped to 123,873 by 1835 - probably half of this going out by the canal, costs being considerably less than road transport e.g. to such places as Macclesfield and Marple and Bollington.

However when the colliery railway links via the LNWR to Stockport and Macclesfield were available after 1845 the proportions of coal sent by canal declined. The canal also suffered the disadvantage of stoppages due to freezing up (e.g. for three weeks in 1835 despite the efforts of ice breaking boats) and sometimes after burst banks the canal had to be drained. The better connections and favourable rates for coal encouraged railway use especially to the main market at Stockport and it seems likely that only the collieries nearest to the wharf, i.e. the Canal Pits, Nelson Pit and Anson Pit, used the tramway connections to the canal wharf. The collieries still found the canal important enough for new (secondhand?) boats to be bought in 1878 and 1882 at costs of£44 and£22. Lord Vernon took the opportunity, when the Canal Company because of its financial difficulties was sold to the railway company, to get the cost of transporting coal fixed at 0.75d per ton per mile. In 1846 about 42,000 tons out of a total of 237,000 sold went out by canal, i.e. 18%. The number of cotton mills in Bollington greatly increased in the 1840s and 50s and it seems the canal then continued to carry up to one quarter of the total coal sold, e.g. 24% in 1869, 19% in 1873. This declined to about 15% in 1880 when of the 20,592 tons which went out by canal 9171 tons was distributed from the boatyard to customers, 1744 tons went for sale at the Bollington coal wharf and 10,915 tons at the Macclesfield coal wharf (both owned by the collieries). Remnants of the latter can still be seen on the west bank south of Buxton Road bridge. In Macclesfield there was also a rail depot which sold 5210 tons. By 1897 there was only 6% sent by canal and cheaper rail rates encouraged all coal sales in Macclesfield to be from the rail depot while for the first time more was sold from the rail depot at Bollington on the railway, opened for goods in 1870. In 1897 the canal's owners changed their name to the Great Central Railway which became part of the London and North Eastern Railway in 1923. Thus the Macclesfield to Marple line from 1871 came to be run by the Macclesfield Committee, one partner of which also owned the canal. The rail connection it formed with the Poynton Collieries, especially after the reorganisation of the colliery railways to haulage by steam in the late 1880s, took away some of the canal traffic.

In 1906 a Royal Commission investigated the future of the canals.115 Mr. Sam Fay of the Great Central Railway noted the speed, accessibility and better longer distance handling of the railways which have "a goods train service of which there was no parallel anywhere in the world...with the exception of extreme Scotland your traffic that is sent today is delivered tomorrow". He felt there was little point in further investment in the canals such as the Macclesfield which his company owned. The carriers in their evidence noted that in general railway ownership was inimical to the best interests of the canals. It was well known they said that railway companies commonly bought canals cheaply when their business declined in face of rail competition, and then let them decline. The Commission's evidence reveals that in 1905 coal was the main traffic, the largest item but only amounting to a mere 123,000 tons, with some traffic in stone, grain from Macclesfield to Manchester, a declining trade in raw cotton from Manchester to mills along the canal, with little traffic in the reverse direction, some lime and limestone and some manufactured goods. There was a loss on the three canals, Ashton, Peak Forest and Macclesfield of£1989 in 1905. This decline continued until 1948 when the British Transport Commission inherited the canal at the time of the formation of British Railways. In 1963 the Commission was abolished and its waterway functions passed to the British Waterways Board. Some records of the early days of the canal survive at the Public Record Office16 (1826-1851) and Charles Hadfield's17 book gives the best account of its general history and more is also included in our longer account.

The canal has always been recognised to have some recreational potential. It provided excellent coarse fishing including contests for local people and angling clubs, popular since mid-nineteenth century. An unusual opportunity to catch fish easily was offered in March 1912 when the banks burst at Bollington and "thousands of fish were hurled out of the canal by the force of the water and were caught in the roads and fields by men, women and children".18 The fine scenery along the canal in the Pennine foothills was recognised by the many botanising and rambling clubs. Westall in one of the earliest books on inland pleasure cruising19 notes it is "admirably adapted to pleasure boating" running "at the foot of the moors through most diversified and picturesque country". For the modest sum of 8s a motor boat could run the whole length of the canal, but Westall dislikes the charge of£1 1s for boats on the short stretch of the Trent and Mersey Canal Hall Green - Kidsgrove, He still includes it in one of his routes for cruising from London to Manchester and one of his round England cruises.

Part of this more active enjoyment of the countryside may be seen along the banks of the canal in High Lane, Poynton and Adlington where many wooden summer houses were erected to be used at weekends and for holidays, these changing in recent times to caravans and an enormous increase in the number of pleasure boats. This important change to successful leisure use, fostered by the British Waterways Board and Cruising Clubs, is symbolised by the conversion of the former coal wharf area into a boatyard which serves the Marina. After the second World War a vigorous movement in which the North West played an important part (see A.H. Body's20 and David Owen's21 books) succeeded in getting the derelict lengths of the Rochdale, Ashton and Peak Forest Canals reopened by 1974 partly by voluntary labour so as to complete the Cheshire Ring.

In 1975 the Macclesfield Borough Council designated the stretch of canal in its area as a conservation area under the County Planning Acts22 thus securing control over building and preserving for generations to come an important amenity of considerable beauty and historical interest for walking and boating.

Pickfords and traffic on road and canal through Poynton

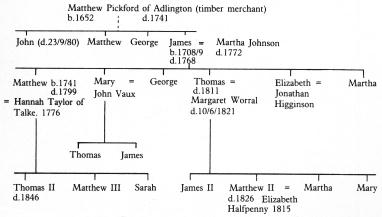

In considering next the important contribution to road transport made by a Poynton family our indebtedness must first be acknowledged to Dr. Gerard Turnbull whose book23 stimulated further local research after correspondence. The name of Pickford is fairly common in the parish Registers of Macclesfield and in the Hurdsfield, Adlington and Poynton areas. A Thomas Pickford was involved in support for the Royalists in the form of horses supplied during the Civil War and in carting stone from Goyt quarries after 1660 for road repair with other goods in the reverse direction on packhorse trains. There is no certainty that he was related to James Pickford, the founder of the famous carrying firm but it seems likely that James' father was Matthew Pickford of Adlington, whose home was probably at Whiteley Heys on the south side of Whiteley Green. Matthew was a successful timber merchant as well as a farmer having premises in Wood Street, Manchester. When he died in 1741 he left, in his will dated 4 December 1740,24 these premises and stock of timber to his two elder sons John and Matthew and two other trustees to be sold. The residue of his estate and the proceeds of this sale were shared equally between his four sons, the youngest of whom was James. The sale is advertised in the Manchester Mercury for 27 July 1742 which says at the end "For particulars enquire of his sons; John Pickford of Poynton, Matthew Pickford at the aforesaid timber yards and Henry Richardson in Norbury". It thus appears that John already lived in Poynton most likely as a farmer at Lostock Hall, - his marriage is recorded in Poynton Parish Register and he was tenant there in the 1770 survey. Many Pickford graves are to be found at Prestbury churchyard not far from the chapel, including probably this John who died on 23 September 1780 and those of James and his son Matthew and their wives.

It seems very likely that this James is the one who held a pew in Poynton

Church and took up a further tenancy from Sir George Warren in 1747. He would

have a substantial inheritance under his father's will which he used partly

to start his farming operations but chiefly to set up as a carrying business

along the Manchester to London route. His family tree and that of his even more

important elder son Matthew is given below. The dotted line is a probable, but

not proved connection.

|

|

Before the era of canals there was a great need to develop facilities to transport cotton and silk goods and also copper to and from Manchester, Stockport and Macclesfield. James' tenancy was at first in the region between London Road and Poynton Green. James and his son Matthew rented larger and larger areas of land until by the time of the latter's death in 1799 he had by far the largest single tenancy with ground rented both from Sir George Warren and Peter Legh of Lyme in Norbury. The records describe James first as a farmer, later as a wagoner. It was common for farmers to have carrying businesses: they had the horses, the wagons, the capital and pasture which was necessary. The business was at first based at Mellors, relics of whose buildings can still be seen at the junction of Clumber Road and Dickens Lane. It is probable that the main traffic route, before the straighter turnpike route was opened in 1762, came via Lower Park Road, the Village, Poynton Green, Clumber Road and the lower part of Dickens Lane to Midway. Besides Mellors James also had a small cottage at Lane Ends by 1770 on the east side of London Road- perhaps he had an office there for his business after the opening of the new road which no longer went past Mellors. By August 1756 James could describe himself as the London and Manchester wagoner with a base in London where he employed a bookkeeper.

"This is to acquaint all Gentlemen, Tradesmen and Others, that James

PICKFORD the London and Manchester Waggoner has removed his Waggon from the

Blossoms Inn m Lawrence Lane to the Bell Inn in Wood Street, Cheapside, from

whence it goes every Wednesday. And his other Waggon goes every Saturday, as

usual, from the White Bear in Basinghall Street.

Each Waggon, for the Carriage of Goods and Passengers, at reasonable Rates,

goes by and through the Towns undermentioned, viz. Newcastle-under-Lyne,

Congleton, Macclesfield, Stockport to Manchester, and delivers Goods etc.

for Ashton-under-Lyne, Oldham, Rochdale, Bury, Bolton and other adjacent

places. At which places Gentlemen etc. may depend on having their Goods. etc

safely delivered. By Your Humble Servant,

JAMES PICKFORD

N.B. No money, Plate, Jewels, China Ware, Glass or Writings will be

accounted for, unless a true Account of them is delivered to the Bookkeeper

and constant Attendance is given every Day at the above said Inns in London

to agree with Passengers to take in Goods.

JOHN JONES, Bookkeeper to both waggons."

James had joined the ranks of one of the few large scale carriers who operated between the capital and an important province, having according to Turnbull's estimate six broad-wheeled wagons each pulled by eight horses with a ninth travelling alongside as a reserve - the wagons being worth probably£180 and the specially bred horses£540. His vehicles took nine days to reach London and eight to return on his twice weekly service. He evidently carried passengers somewhat uncomfortably as well as goods. Poynton was a convenient base not far from his northern terminus where vehicles and animals could be looked after by local craftsmen - there was a well established smithy at Poynton Village and Midway (see Smithy Field on the sketch map). The route from Manchester had been turnpiked to Hazel Grove in 1724. When from there to Sandon was turnpiked in 1762 Pickford's wagons began to run via Leek, Ashbourne and Derby to London using other turnpiked roads. James had a setback in 1757 and put his wagons up for sale, but recovered after the opening of the turnpike road heading the list of carriers in advertisements in 1765 which put up prices because of increased tolls on broadwheeled wagons, expenses for fodder, and restrictions on weights allowed.

In 1768 James died intestate aged 59 but his successful business passed first to his wife Martha who died in 1772 and then her son Matthew "in consideration of the aid and service afforded in and about the said business". Matthew, then 32, had probably become deeply interested in and mastered all the details of his father's business. He had made the right connections and knew the routes well - he probably met Hannah Taylor, his wife from 1776, at Talke near Newcastle under Lyme on his travels. Now followed a period of most daring expansion, helped by the enormous increase in trade at the time of the industrial revolution, the further turnpiking of roads and the success of canals on the routes. In 1777 he increased the service to London to three times a week and in 1788 to every weekday. By using flywagons which he developed he was able to reduce journey times progressively to 4.5 days by 1776 (about 42 miles a day). These brought the advantages of the lightness and better springing enjoyed by coaches while retaining the capacity to carry substantial loads and also a few passengers at a cheap rate - only four horses were needed. Later in the 1800s the even lighter flyvan was used which being built on stage coach lines could carry lighter parcels in 36 hours - leaving slower vehicles for the bulkier loads. By 1799 Matthew had increased Pickford's share of the London carrying trade to one third.

During the years 1775-1803 he tried his luck with passengers and small parcels traffic with a coaching service to places like Bath, Birmingham, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Leeds, Liverpool and even a Blackpool coach departing every morning at 6 a.m. via Bolton and Preston. There is a certain flamboyance in the following advertisement in 1777:

"A new and excellent Diligence is advertised from Upper Royal Oak Inn, Manchester to London to carry 3 persons at 2s 6d each three days a week via Poynton and a flying coach on Tuesday and Thursday, inside passengers£1 16s, oumde£1 1s ... taking 2 days from 4 p.m., performed (if God permit) by Mr. Pickford of Pointon" and other agents along the route. After the mail coach system replaced post boys and riders in 1784 Matthew became responsible for providing horses and drivers for the daily Royal Mail coach for its passage from Manchester to Macclesfield. The coach built to a special design and, gaily coloured with an armed guard provided by the Post Office, must have been a lively sight on its northward journey in the evening through Poynton in charge of locally known men and horses. The journey time allowed for this section was 2 hours 35 minutes, i.e. almost 8 m.p.h. The journey south was made in the small hours. Journey times were gradually reduced - by 1808 the whole journey to London took 28 hours.

In the 1790s Matthew became interested in association with Nathaniel Wright, who held the mining rights, in canal projects which were being proposed to help transport coals from Norbury and Poynton to Stockport. He probably offered capital as he is named as one of the lessees25 and support by leasing from the Leghs of Lyme the fields marked on the sketch map which formed the Norbury Hall property in which substantial canal works were proposed in 1795. With the aid of the Land Tax records26 it is possible to identify the large amount of land Matthew held. The main elements remained the Mellors Farm, increased to 47 acres in size, and which by 1784 he had purchased from Sir George Warren, and Birches Farm of 154 acres but with other substantial holdings probably amounting in 1784 to over 500 acres, some of which like Barlow Fold Farm he only leased for a few years. Birches Farm at Midway on the new turnpike road which was leased from Sir George had by now become the main operating base for the business where stables and perhaps repair facilities, and arrangements for feeding and watering horses en route were set up. We know that in 1803 of Pickford's 262 horses not actually on the road at any one time 20 were stationed in Poynton though the major stables were then at Leicester (30), Stony Stratford (60) and London (100). The farm at Birches was by 1810 sufficiently grand to be listed as a gentleman's seat in the guide books of the time.27

Perhaps the most courageous move made by Matthew was to seize the opportunity for transport provided by the extending network of canals. He did not wait till all the canal projects were completed but combined land and water carriage to remedy deficiencies in canal routes until new stretches of canal were completed. For example, by 1786 his canal boats were sent from Manchester via the Bridgewater and Trent and Mersey canals to Rugeley where goods were transferred to his road vehicles and he later used the Coventry, Oxford and Grand Junction Canals. By 1803 Pickfords owned 28 boats and 50 wagons. Matthew also increased his local road carrying services in the textile areas by running a second wagon to Leek three times a week, and a third wagon to serve Buxton, Ashbourne and Derby, all areas where no canals were yet available. Matthew's brother Thomas by 1780 had been installed to run the London end of the business - buying the Castle Inn and making it Pickford's London headquarters. At the Manchester end after various changes Pickfords had offices in Fountain Street, warehouses in Market Street and a small warehouse at Castle Quay, the terminus of the Bridgewater Canal.

When he died in 1799 Matthew was described in the Manchester Mercury as "The London carrier - in which branch of business he was one of the most extensive proprietors in the kingdom". His wife Hannah continued to reside at Birches Farm until her death in 1819 and his estate was to be shared equally between his three children Thomas II, Sarah and Matthew III. From then on there was a gradual decline in the success and interest of the Pickford family in the business. Thomas who was more interested in farming retired at the London end, which was taken over by his two sons James II and Matthew II while Matthew's own sons managed the Manchester end from Poynton. For 15 years however the business expanded especially on the canal side after the Blisworth tunnel was opened in 1805 to complete the Grand Junction Canal. Pickfords established major sub depots along the chief canal route including one at Macclesfield. The flywagons and light vans appear to have been successful. Thomas II by 1809 had moved to live at Deanwater and by 1819 had moved again to Ashley Hall.

By 1817 however Pickfords were in desperate financial trouble - the new generation evidently lacked Matthew's financial skill and business acumen in face of very severe competition. Fresh capital from new partners had to be sought and the firm was gradually restored by the greater financial and managerial skills of Joseph Baxendale who became a partner and assisted Thomas at the Manchester end, along with Zachary Langton who joined Matthew III in London and Charles Inman who took over the large Leicester base. By the 1830s Poynton had ceased to be an important base especially as services were now operating on a much wider scale, e.g. to Sheffield via Hazel Grove where some of the horses now came to be based instead of Poynton at the junction of two important roads. Thomas Landor had succeeded Edward Smyth at Birches Farm as manager of the Manchester to Leek vehicles and the stables at Poynton. An interesting ledger is preserved along with other Pickford papers28 in the Public Record Office for the period 1817-1822. This shows Thomas Landor received£564 for horsing the Manchester to Leek van for a period of 92 days, 64 miles per day at 1s 11d per mile. Pickfords also paid Martha Pickford or sons for hay used by the horses (£38 for seven tons per quarter in 1817), rent for the stables for the six remaining horses,£40 and an additional fee for "caravan" stables and ostlers at Poynton. A little local shoeing was still done by Martha Wood, blacksmith (at the Village?).

With the opening of the Macclesfield Canal in 1831 Poynton residents would see some of the fleet of Pickford's boats passing through - as we have seen they took part in the opening ceremony - but all boats were withdrawn by 1845 because railways were more efficient. Thomas II and Matthew III who remained longest in the business after 1817 continued in deep financial trouble and were only saved from bankruptcy by their new partners.

By 1823 the headquarters of the firm was transferred to the canal depot at City Basin in London. The last Pickford connection with the firm passed with the death of Thomas II who held a quarter share until his death in 1846. "Fhe name was so well established however that it was retained and the rest of their story including the major change to working as subsidiary carriers for the LNWR and taking on removals work may be studied in Turnbull's work.

It is interesting with the aid of directories, invoices and records relating to Pickford's business to note some examples of passenger, mail and goods traffic through Poynton in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. We have seen that Pickfords took part in some of the coach services and the combined mail and passenger services to London and places in between from the year 1777 at least. By 1794 there were also shorter routes, e.g. the 1794 Manchester directory states "The Macclesfield Accommodation coach every Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday afternoon at 6.0 p.m. reaches Macclesfield about 9 p.m. and leaves next morning at 6 a.m.". In 1797 the Pack Horse Inn, Poynton Lane Ends is advertised as a place where coaches stopped. By 1800 the Royal Mail left Manchester daily now at 1 p.m. taking 28 hours to London and also the Royal Telegraph at 7.30 a.m. daily taking four passengers inside "with lamps and lighted all the way", taking 31 hours, and a coach to Birmingham, Monday, Wednesday and Thursday at 9 p.m. In 1804 fares on the Defiance, which left at 4 p.m. were to Macclesfield 10s, to Derby£1 8s Od, London£3 3s Od, inside, about half this outside. Small parcels cost 6d, 1s and 2s and large 0.5d, 1d and 3d per lb. on this and the Royal Mail coach to the same destinations, but the Mail only had inside passengers. There was also a Royal Telegraph coach with four passengers which left Manchester at 4 p.m, 29 hours to London, and a coach three times a week, the John Bull. The picture shows a broad-wheeled wagon and other typical vehicles in Market Street, Manchester, about 1828 with possibly a London coach setting off from the Royal Hotel, then the most important starting point.

As the route via Wilmslow improved some of the Birmingham and Shrewsbury coaches began to go that way, but by 1837 at the time of fullest expansion of coach services before the local railways took over the traffic there were besides the London coaches passing through Poynton the Royal Macclesfield, Fair Trader, Brilliant, Hero, and True Briton to Macclesfield, the Honeycomb and Independent Potter to the Potteries and the Express to Birmingham. Even after the railways came there still remained a place for road transport in the more populated areas. Following the invention of the horse omnibus in Salford by 1857 there were 12 services a day between Stockport and Manchester, and by 1890 the first horse drawn trams were in operation between Stockport and Hazel Grove. A service of wagonettes developed from Poynton to link up with these vehicles especially after the Hazel Grove trams were absorbed by Stockport Corporation in 1905 and their route electrified. The route was electrified as far as the Rising Sun by 1911 and brought many visitors to Poynton and Middlewood. For a brief heady period in 1913 there was even talk of a tramway to Macclesfield with a branch up Park Lane, but by 1914 a regular motor bus service was running to link with the trains at Hazel Grove on Saturdays. Private motor transport was sufficient to support the first motor omnibus proprietors in Poynton and public transport had started to Stockport by 1928. The picture shows an omnibus as well as private car near John Shrigley's garage in London Road (now Poynton Motors).

One of the firms which used Pickfords wagons was John Swanwick, drapers of Macclesfield. Among invoices surviving from this firm29 are items for various cloths wrapped in canvas bales such as cassemere (a twilled woollen cloth),, velvet from firms in London, silk nap from Gloucester, women's silk hose from Loughborough, feathers from Uttoxeter between 1788 and 1806. For a silk manufacturer in Macclesfield, Thomas Bullock, bales of silk, boxes of glass, chests of tea, bags of malt were transported by Pickfords in the 1820s for the mill and household. Bales weighing about 1 cwt. cost 5s 6d to 6s 6d for the journey to London. Pickfords own records in the period 1810-1840 add to the list the following industrial products, bales of cotton, cotton twist, wool, cutlery, colours, hemp, flax, glue, gum in hogsheads, madder in casks and at the time of the Peterloo massacres thousands of swords and pistols with which gentlemen armed themselves against attacks. General goods and raw materials carried include paint, oil, leather, blacksmiths' requirements, molasses, iron liquor, candles, seeds, butter, cheese, fruit, eggs, ground plaster, grain in bags, borax, cobalt, tallow, tar, resin, hops, ashes, manganese and logwood. Bulkier items Manchester to London cost 50s-70s a ton, gents' goods such as drapery, tea, tobacco, wines and spirits, 80-85s a ton, military stores, furniture, silk 90s and hats 140s in 1828. Similar goods were no doubt carried by the many other carriers using the turnpike road.

Accidents are frequently reported - the loss of drivers and nine horses in disastrous floods at Stony Stratford in 1809, or the death of a driver of the Sheffield wagon who was walking by the side of his vehicle on Lancashire Hill, Stockport when the axle tree broke and the wagon fell on him. Matthew III patented an improved roller bearing system in 1822 designed to reduce friction at this vital point. Speeding and racing by rival vehicles caused accidents, e.g. a Pickford's wagon was "knocked to pieces in a race by the driver against a mail coach in St. Albans in 1818".

Theft from wagons and boats is recorded, e.g. a pack containing muslin, handkerchiefs, shawls and calico was stolen from a porter's cart in Manchester in 1799. In 1839 two Pickfords' boatmen were hung for a horrible assault and murder of two female passengers in Rugeley and thieving from boats was said to be an accomplishment with receivers available at all points along the canal.

Nevertheless it was a considerable feat by the carriers to provide horse drawn transport on canal and road sufficient to satisfy the demands for manufacture and distribution at a time of enormous expansion especially in the North West. In conclusion the following extracts from an article in the Penny Magazine in 1842 give the flavour of detailed and efficient organisation at Pickfords' headquarters in London - which no doubt would have pleased its Poynton founders James and Matthew. The account is illustrated by a map first published in 1828 showing the extent of their canal and road network. The road through Poynton was still their main artery.

"From about five or six o'clock in the evening waggons are pouring in from

various parts of town, laden with goads intended to & sent into the country

per canal In the morning, on the other hand, laden waggons are leaving the

establishment conveying to different parts of the metropolis goods which

have arrived per canal during the night.

On entering the open area we find the eastern side bounded by stabling,

where a large number of horses are kept during the intervals of business. In

the centre of the area is the general warehouse, an enormous roofed building

with open sides; and on the left are ranges of office and counting-houses.

To one who is permitted to visit these premises there is perhaps nothing

more astonishing than to see upwards of a hundred clerks engaged in managing

the business of the establishment; exhibiting a system of classification and

subdivision most complete.

Hence arises a most extensive system of correspondence and supervision in

which all the branch establishments look up to the parent establishment in

London. In one of the offices of the counting-house, for example, the wall

is covered by folios or cases, each inscribed with the name of one

particular district, and each devoted to the reception of letters, inquiries

and other communications from the managers of the branch establishment to

which it relates".

All these transport activities in Poynton gave work for a fair number of grooms, drivers of various kinds, blacksmiths, shoesmiths and saddlers, as well as a great deal of colour and excitement to life.

References

1. Bennett, J.H.E.(Editor). Quarter Sessions Records for the County Palatine of Chester 1559-1760. Vol. 1. County Records Sub-Committee, 1940.

2. Dodd, A,F. and E.M. Peakland roads and trackways. Moorland, 2nd ed., 1980.

3. Young, Arthur. Six months tour through the North of England. Vol. 4, 1771.

4. Adlington Womens Institute, How old are your hedges (a chart), 1978.

5. Sandon-Bullock Smithy Turnpike Trust Principal Act. 26. 111.

6. Sandon-Bullock Smithy Turnpike Trust Records. Staffs Record Office, D.706, D.745 and D.1411 + accounts of Macclesfield District at QDT 3/22 CRO.

7. Articles of agreement for repair of bridges. QAR 15 & 34 CRO.

8. Bird, Anthony. Roads and vehicles. Longman, Industrial Archaeology Series, 1969.

9. Poynton and Worth Parochial Records, CRO P.C. 20.

10. Prestbury Highways Board and Macclesfield Rural District Council Records. LRM 2472 & 2738 CRO.

11. Chesterman, R.G.A. Laughter in the House. Local taxation and the motor car in Cheshire 1888-1978. Cheshire C.C., 1978.

12. British Waterways Board. Cruising on the Macclesfield Canal. Inland Cruising Bulletin No. 11, 196?

13. Nicholson's Guide to the Waterways, No.2 North West. British Waterways Board, 1972.

14. Macclesfield Canal Acts. Principal Act, 7 George IV Cap. XXX.

15. Royal Commission on Canals and Inland Navigations in the U.K. Reports and evidence. H.M.S.O., 1906.

16. British Transport Commission. Records of Macclesfield Canal at PRO Kew. BTH RAIL 850.

17. Hadfield, Charles. Canals of the West Midlands. David and Charles, 1966.

18. Stockport Advertiser, March 1912.

19. Westall, G. Inland cruising on the rivers and canals of England and Wales. Westall and Co., 1908.

20. Body, A.H. Canals and waterways. Greater Manchester Council, 1975.

21. Owen, David. Canals to Manchester. David and Charles, 1966.

22. Macclesfield Borough Council Planning Dept., Macclesfield Canal conservation area, an illustrated booklet, 1975.

23. Turnbull, Gerard. Traffic and transport. An economic history of Pickfords. Allen and Unwin, 1979.

24. Will of Matthew Pickford of Adlington, WS 1641 CRO.

25. Lease of mining rights in 1793 from Sir George Warren to Nathaniel

Wright and Matthew Pickford. Legh papers. Box TD/1 John Rylands Library.

26. Land Tax Records for Poynton, Worth and Norbury, QDY2 CRO.

27. Cooke, George Alexander. A topographical and statistical description of Cheshire. The author, 1810.

28. Pickfords' records, BTH RAlL 1133 PRO.

29. John Swanwick, drapers, records in the possession of Mrs. Marie Moss and

invoices of Thomas Bullock, silk manufacturer, in possession of D.A.

Kitching.

This text taken from: Poynton A Coalmining Village; social history, transport and industry 1700 - 1939, by W.H.Shercliff, D.A.Kitching and J.M.Ryan, published by W.H.Shercliff, 1983. ISBN 0 9508761 0 0

Chapter 7. Subsidiary Industries managed by the Colliery Administration

Chapter 9. Poynton Railways

Last updated 9.11.03